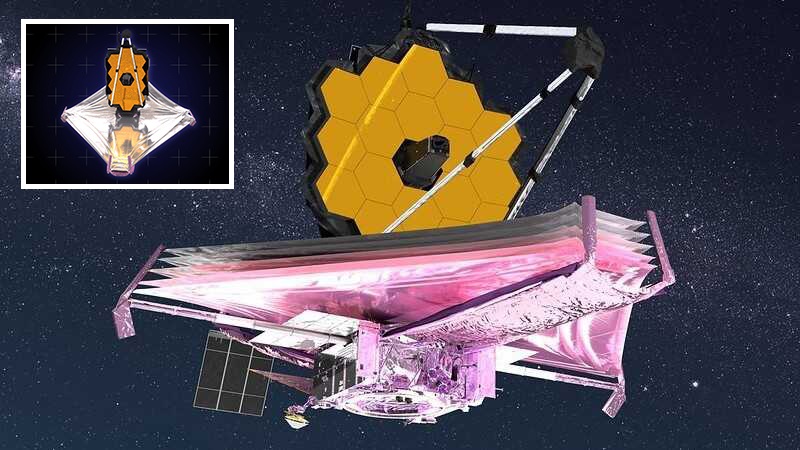

The second mid-boom of the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) mission was successfully deployed by NASA shortly before the clock struck twelve in the year 2021. The telescope’s sun shield has grown to its full diamond form in orbit after passing the milestone.

During the year of 2021, NASA had a busy and fruitful schedule. Watching the Mars Perseverance Rover’s dramatic landing on the red planet earlier this year was a thrilling experience for many. The Ingenuity Helicopter, which was attached to Perseverance’s belly, made its maiden flight only a few months later.

The Double Asteroid Redirection Test (DART) launched in late November and started its long trip to ram with asteroid Dimorphos in preparation for a possible apocalypse scenario. Parker Solar Probe became the first human-made spacecraft to come within a few thousandths of touching the sun on December 15.

Finally, on Christmas Day, the James Webb Orbit Telescope finally launched into space after two and a half decades of hard effort. The diamond-shaped sunshield for JWST was installed by NASA towards the end of 2021, marking an important achievement for the mission.

Shine bright like a diamond 💎

With the successful deployment of our right sunshield mid-boom, or “arm,” Webb’s sunshield has now taken on its diamond shape in space. Next up: tensioning the 5 sunshield layers! https://t.co/6G2caS1djY #UnfoldTheUniverse pic.twitter.com/q0iuHdnKlN

— NASA Webb Telescope (@NASAWebb) January 1, 2022

Two days after completing its first week in orbit, the sunshield of JWST was unfurled. In order to pull off this incredible achievement, 107 sunshield deployment membrane release mechanisms have to work without a hitch. NASA was on pins and needles when the motor-driven mid-booms emerged and dragged the sunshield’s folded membranes along. This enabled the sunshield to completely stretch over the observatory to its 47-foot width.

“The mid-booms are the sunshield’s workhorse and perform the heavy lifting to unfold and draw the membranes into that now-iconic shape,” says NASA Goddard Space Flight Center observatory manager Keith Parrish.

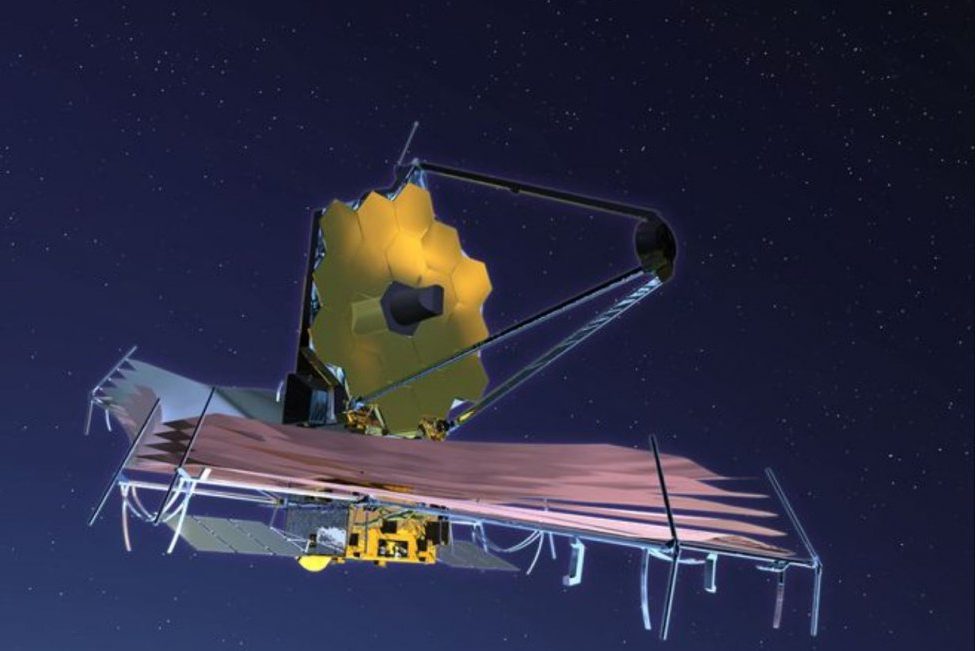

The expedition would not have been able to continue without the sunshield taking form and settling into place. Using infrared radiation from weak and distant objects, JWST will generate the images that astronomers and scientists hope for. It must be kept extremely cold to insulate it from the Sun, Earth, and Moon’s heat and light sources in order for this to work. The shade will be provided by the sunshield, which is the size of a tennis court.

The sunshield will constantly be between JWST and the Sun, Earth, and Moon as it travels. Because JWST will be circling the Sun at a distance of 1.5 million kilometers from Earth, precise positioning will be attainable. Passive heat radiation from the sunshield will maintain the telescope at a temperature of less than 50 Kelvin (-370 F or -233 C).

There are five levels to account for this. Heat is absorbed by certain layers and then radiated forth by others. Very little heat will ever reach the telescope and its equipment as a result of this operation.

Kapton is used to make the five layers. The aluminum is then applied to all five layers, with a “doped silicone” coating applied to the sun-facing side of the two hottest layers to reflect the Sun’s heat back into space. DuPont developed Kapton, a polyimide film, in the late 1960s.

A broad variety of temperatures does not destabilize the material, despite its strong heat resistance. The substance is impervious to even the most extreme heat. It is also employed in a wide range of electrical and electronic insulating applications because of these qualities.

It is also crucial to consider the form, quantity, and spacing of the layers. There are five layers that work together to achieve their specific tasks. On a NASA-sponsored panel at the Goddard Space Flight Center in Maryland, James Cooper, the JWST Sunshield Manager, noted “Shape and design help drive heat out the sides, along the perimeter, and between the layers. Objects cannot be heated by the “core” heat created by the Spacecraft bus. This heat is driven out between the membrane layers.”

Despite this little setback, the sun shield rollout was completed on schedule. The operations group made the decision to go slowly and cautiously. Parrish said, “Why do we keep saying, “We do not anticipate our deployment timeline will change but we expect it to change?” because of today? We stopped, assessed the situation, and then proceeded methodically with a plan, as we would practise for just such a scenario. In terms of deployment, we still have a long way to go.”

As the observatory continues to take shape, the NASA crew will approach each new milestone with trepidation and anticipation. They are acutely aware of the criticality of every component working well in order for the mission to be a success. According to the ancient adage, it is better to be safe than sorry. Patience and meticulous preparation will be necessary at every stage of JWST’s complete implementation since so much is relying on it.

After successfully extending booms for the spacecraft’s sunshield, NASA will take a one-day pause from the deployment of the James Webb Space Telescope.

In a statement on Jan. 1, NASA said it will begin the process of tensioning the five-layer sunshield, putting it in its final shape and ensuring that the layers are isolated from each other. It will take at least two days to accomplish that endeavour, which is currently planned to begin on January 2.

After working through the night on Dec. 31 to extend two “mid-boom” structures on each side of the spacecraft, mission management included a halt in the sunshield deployment. The sunshield’s length was increased by the booms. Sensors revealed that a sunshield cover had not yet completely folded up, which sparked this operation. The removal of the cover was found to be consistent with data from temperature sensors and gyroscopes, so controllers opted to go ahead and deploy the booms.

On Dec. 31, JWST observatory manager Keith Parrish of the Goddard Space Flight Center remarked that the crew has practiced “stop, analyse, and move ahead systematically with a plan” when faced with this kind of event. “This deployment procedure is far from over,” he said.

Since its launch on December 25, the spacecraft’s lone problem has been a sensor malfunction. The sunshield deployment depended on 107 membrane release mechanisms, each of which had to operate in order for the sunshield to expand. According to the agency, all 107 were successfully freed.

NASA said that the one-day delay in finishing the sunshield tensioning will certainly delay other tasks. Sunshield deployment is now complete, and the controllers will proceed to the next step: installing the telescope mirrors. One-day delays will have minimal long-term effect on the mission, which will spend six months finishing the telescope and its equipment’ commissioning..

On Dec. 31, Parrish made a statement on the boom deployment in which he said that “today is an example of why we continue to emphasize that we do not believe our deployment timeline could change, but that we anticipate it to change.”