Following the first test of an iodine-based thruster in space, iodine might one day propel and position constellations of mini-satellites.

The system provides a less expensive, more adaptable, and more efficient propellant alternative for satellite maneuvering than conventional electric thruster systems, which mostly depend on xenon.

‘Iodine is a game-changing propellant, and our results indicate for the first time that it is not only a feasible alternative for xenon, but also provides improved performance,’ says Trevor Lafleur, lead engineer at ThrustMe, the French firm that developed the technology.

Ion drives are commonly employed on tiny satellites due to their great fuel economy. In order to move, alter orbit, and avoid collisions, they typically use solar power to electrically accelerate the ions of a propellant gas.

Because of its comparatively large atomic mass (131), xenon has been the propellant of choice in such systems, which is required to create a high power-to-thrust ratio. Xenon is also appropriate since it ionizes fast, limiting power losses during plasma formation. Furthermore, it is a chemically inert gas with very little reactivity and toxicity.

In the space business, however, there is an increasing tendency toward even smaller spacecraft that create networks, or constellations, of satellites. Due to xenon’s rarity and high cost, there is concern that future demand could result in significant price volatility and supply issues.

There are also fears that launching satellites into space without propulsion capability would result in more in-orbit collisions and space debris. According to some predictions, 24,000 satellites will be deployed in the next ten years. ‘At the moment, many tiny satellites have little or no propulsion due to storage issues with gaseous propellants like xenon,’ adds Lafleur.

‘Ion thrusters were utilised less until the past five years, so xenon could be employed with scarcity being less of a concern,’ says Charlie Ryan of the University of Southampton, who designs tiny spacecraft propulsion systems. However, because to the fast-paced expansion of the space industry, xenon consumption is becoming unsustainable.

Solid solution

Researchers have been looking into utilising iodine, which has a high atomic mass of 127, as an alternative propellant for around 20 years. Iodine is significantly more prevalent and less expensive than xenon, yet it has three times the density of xenon, even under pressure.

Furthermore, because iodine is a solid at room temperature, it does not pose an explosion danger or need large high-pressure storage tanks, implying that iodine-based systems will be simpler and smaller.

However, because to different engineering obstacles, it has only been tested on the ground up until now. One is that it corrodes the containers in which it is stored. Another issue is that solid iodine must first be sublimated in the harsh conditions of space to generate the propellant gas. Its plasma chemistry is much more complicated than that of xenon, and many of its physical characteristics are unknown.

‘While others have created comparable systems, ThrustMe is the first to tackle the engineering problems of employing this difficult-to-handle propellant and test it in space,’ Ryan explains. ‘It also offers considerable storage benefits, making it an excellent candidate for tiny satellite propulsion,’ says the company.

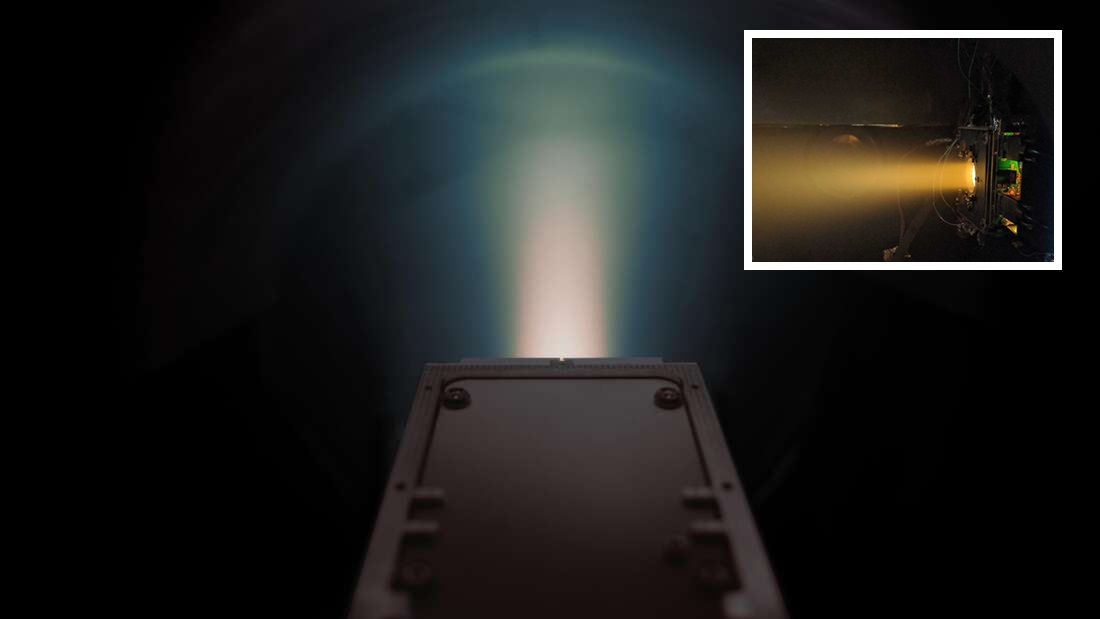

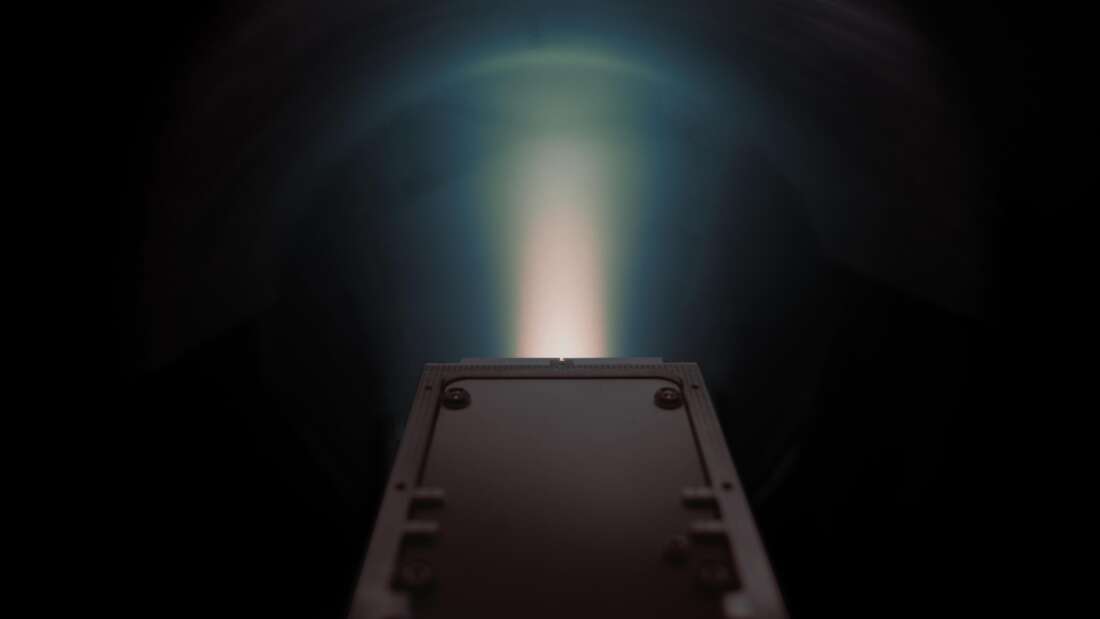

The electric thruster from ThrustMe works by heating solid iodine to a gas with only 1 watt of electricity. The gas is then forced into a chamber where it is blasted by electrons created when a radio frequency antenna is powered up. The ensuing electromagnetic field accelerates the electrons, resulting in two electrons and a positively charged iodine ion being generated when they collide with an iodine gas molecule, forming plasma.

Positive ions are collected from the plasma and pushed to extremely high speeds toward an exhaust, producing thrust. Excess electrons are discharged into the exhaust plume to prevent the propulsion system and spaceship from charging up.

In November 2020, ThrustMe deployed its device into orbit as part of a Chinese aircraft-tracking satellite. The thruster was successfully fired for the first time at the end of December 2020, followed by numerous additional test firings in the months that followed. ‘We were really delighted when we found out that the propulsion system was working well and that we were seeing the first results of an iodine electric propulsion system in space,’ Lafleur explains.

‘This is an interesting conclusion,’ says Benjamin Jorns, an electric propulsion researcher at the University of Michigan in the United States. ‘The authors have demonstrated that many of the recognised technical difficulties – performance decreases and flow delivery challenges – can be resolved.’

‘I anticipate this having a significant influence on the small satellite sector.’ Providers are always on the lookout for technology like these that may make their spacecraft more cost-effective and safe,’ adds Jorns. ‘With that stated, one of the more intriguing problems in the near term will be determining if the performance metrics from a low-power system like this will be sufficient to meet the mission criteria for spacecraft suppliers.’