SpaceX established a new milestone on Thursday by successfully launching 48 Starlink internet satellites and two BlackSky optical Earth-imaging spacecraft into orbit from Cape Canaveral, setting a new record for the most flights by the company’s Falcon rocket family in a year.

At precisely 6:12 p.m. EST, the two-stage Falcon 9 rocket launched from pad 40 at Cape Canaveral Space Force Station, reaching a height of 229 feet (70 meters) (2312 GMT).

The Falcon 9 passed the seashore launch facility and arced downrange northeast over the Atlantic Ocean, emitting an orange light and a ground-shaking rumbling seconds later. With 1.7 million pounds of force, the rocket was launched into a bright late fall sky by nine Merlin 1D main engines using a combination of kerosene and liquid oxygen propellants.

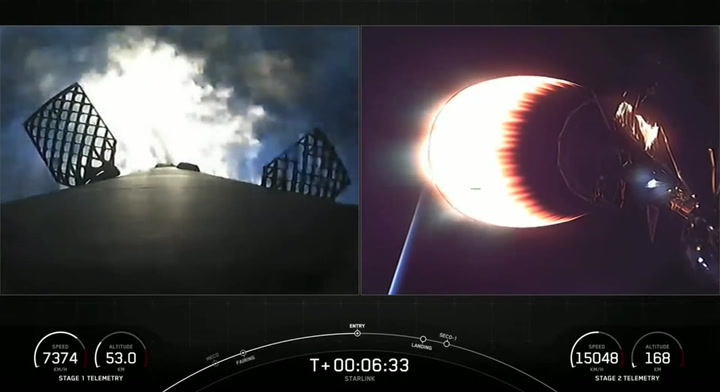

Moreover, two and a half minutes after liftoff, the Falcon 9’s first stage, which was 15 floors tall, shut down its nine engines and separated from the upper stage. The 50 satellite payloads were then sent into a parking orbit by the upper stage’s Merlin engine, which took less than 10 minutes.

Meanwhile, the Falcon 9’s reusable booster stage coasted to the pinnacle of its ballistic trajectory before coming down into the atmosphere at a speed of around 5,000 miles per hour (8,000 kilometers per hour).

Braking operations using three, then one, of the first stage’s engines, slowed the rocket enough for a precision landing on SpaceX’s football-field-sized drone ship “A Shortfall of Gravitas” in the Atlantic Ocean east of Charleston, South Carolina.

After its ninth flight to orbit and back, the first stage, known as B1060 in SpaceX’s fleet, returned to Earth. With the rocket, the drone ship will return to Florida’s Space Coast, where SpaceX will check and refit it for a future mission assignment.

Downrange in the Atlantic Ocean, a SpaceX recovery ship was stationed to collect the two parts of the Falcon 9 rocket’s payload fairing, which the firm also reuses. On Thursday’s mission, the fairing shells were brand new.

The top stage of the Falcon 9 rocket coasted halfway around the globe, passing over Europe, the Middle East, and the Indian Ocean before briefly restarting its engine approximately an hour into the mission near the coast of Australia.

According to altitude data presented on SpaceX’s live launch webcast, the second upper stage engine fired, circularising the rocket’s orbit at roughly 270 miles (440 kilometers).

The last part of the mission, the satellite deployment sequence, was put in motion as a result of this.

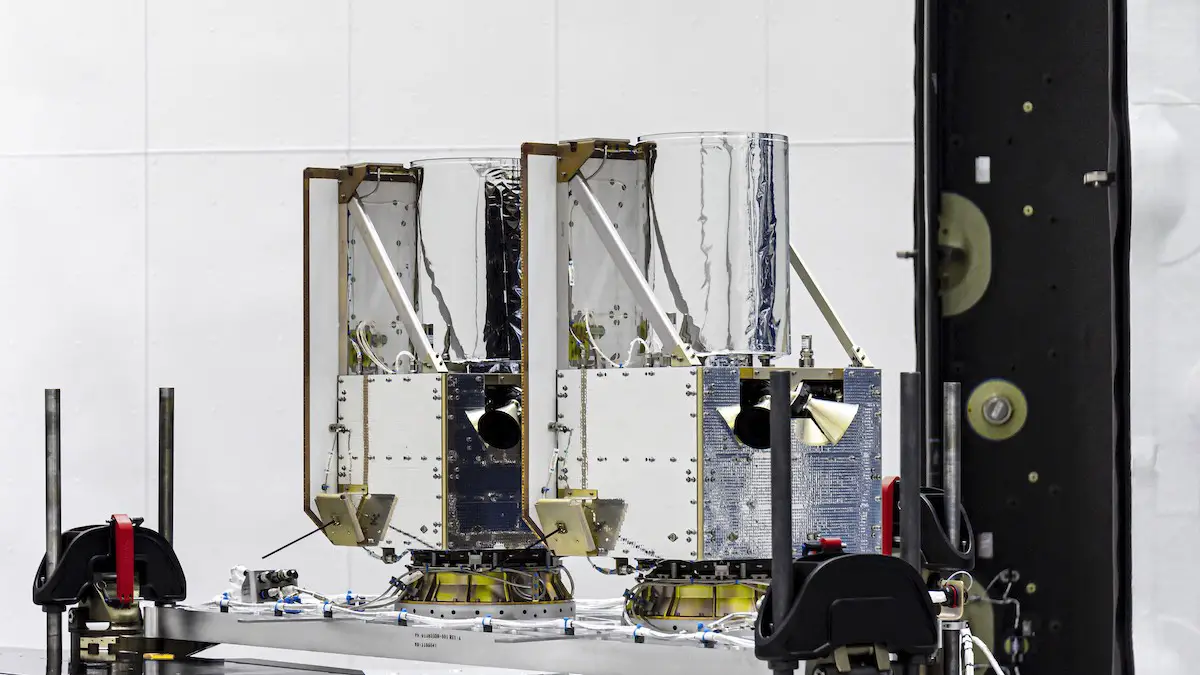

The rocket first fired the two 121-pound (55-kilogram) BlackSky satellites that had been attached to the top of the Starlink satellite stack. At T+plus 63 and T+plus 67 minutes, the twin satellites detached from the rocket, each with an optical imaging telescope for Earth studies.

While flying beyond the range of SpaceX ground stations, the upper stage then released the cluster of Starlink internet stations around 7:41 p.m. EST (0041 GMT), approximately 89 minutes after liftoff. When the rocket sailed over a monitoring point at the company’s Starbase installation in South Texas, SpaceX verified the deployment of the Starlink satellites a few minutes later.

The on-target satellite deployments capped SpaceX’s 27th Falcon 9 launch of the year, breaking the previous record of 26 Falcon 9 flights achieved last year.

Before the end of December, SpaceX plans to launch three additional Falcon 9 rockets from Florida’s Space Coast.

On Dec. 9, NASA’s Imaging X-ray Polarimetry Explorer, or IXPE mission, will launch from pad 39A at Kennedy Space Center. The IXPE spacecraft is equipped with three X-ray telescopes that will study the circumstances around black holes and neutron stars, which are among the universe’s most severe settings.

On Dec. 18, another Falcon 9 rocket will launch with the Turksat 5B geostationary communications satellite from Cape Canaveral Space Force Station. From Kennedy Space Center, a SpaceX cargo mission to the International Space Station is set to launch on Dec. 21.

Later this month, SpaceX might launch another Falcon 9 rocket from the Vandenberg Space Force Base in California. That mission, which will deliver another batch of Starlink satellites into orbit, has no set launch date.

SpaceX has transported 1,892 spacecraft to orbit for its privately-funded global broadband network with the launch of 48 additional Starlink satellites on Thursday night. This statistic excludes failed satellites and other Starlink vessels deorbited by SpaceX.

Starlink Group 4-3 was SpaceX’s 32nd Falcon 9 launch since May 2019, and it was mostly devoted to delivering Starlink satellites to orbit.

The majority of the Starlink satellites launched thus far have landed in a 341-mile-high (550-kilometer) orbit with a 53-degree inclination, the first of five orbital shells SpaceX aims to use to complete the Starlink network’s full deployment. With a series of Starlink missions from Cape Canaveral from May 2019 to May this year, SpaceX completed the launch of satellites in that shell.

SpaceX has been rushing to finish the construction of new inter-satellite laser terminals for all future Starlink satellites since May. The laser crosslinks, which have already been tested on a few Starlink satellites during previous flights, would lessen SpaceX’s internet network’s dependency on ground stations.

The ground stations are costly to set up and have geographical — and occasionally political — limitations on where they can be placed. The Starlink satellites will use laser connections to transmit internet traffic from spacecraft to spacecraft across the globe, eliminating the requirement for signals to be relayed through a ground station linked to a terrestrial network.

Consumers who have joined up for a beta testing program are presently receiving interim internet services through the Starlink satellites.

On a Falcon 9 rocket from Vandenberg Space Force Base in September, SpaceX launched the first batch of 51 Starlink satellites into a 70-degree inclination orbit. At a height of 354 miles, that orbital shell will ultimately house 720 satellites (570 kilometers).

Aside from the 53-degree and 70-degree orbital shells, SpaceX’s additional Starlink layers will contain 1,584 satellites at 335 miles (540 kilometers) with a 53.2-degree inclination and 520 satellites distributed over two shells at 348 miles (560 kilometers) with a 97.6-degree inclination.

The objective of the mission The 53.2-degree inclination orbit, slightly deviated from the 53-degree inclination planes occupied during the first phase of the Starlink network deployment, was the goal of the second Starlink voyage on Thursday night. The previous Starlink launch on Nov. 13 was the first to enter the orbital plane with a 53.2-degree tilt.

The Federal Communications Commission has given SpaceX regulatory certification for about 12,000 Starlink satellites. The company’s first aim is on deploying 4,400 satellites using Falcon 9 rockets in a series of missions. SpaceX’s next-generation launcher, the Starship, a massive rocket that has yet to reach orbit, might be charged with launching hundreds of next-generation Starlink satellites on a single flight in the future.

The two remote sensing microsatellites that rode the Falcon 9 rocket into orbit on Thursday night join eight others in BlackSky’s operational constellation.

Two BlackSky satellites were launched on a Rocket Lab mission from New Zealand on Nov. 17, and Rocket Lab expects to launch two additional BlackSky payloads next week.

In a statement, BlackSky claimed that expanding the constellation “would boost the company’s geographic capacity for data while enhancing client revisit rates.”

In less than three weeks, the company’s fleet of BlackSky satellites will grow from six to twelve, doubling the size of the company’s fleet.

Two more BlackSky satellites are scheduled to launch in early 2022 on a Rocket Lab mission. The remote sensing firm has placed another order with LeoStella, a company situated in Tukwila, Washington, a suburb of Seattle.

BlackSky and Thales Alenia Space, a prominent European satellite maker, have formed a joint venture called LeoStella.

BlackSky, based in Seattle and Herndon, Virginia, is developing a fleet of tiny remote sensing satellites to offer commercial and government customers high-resolution Earth pictures. Within a few years, the business intends to have a fleet of 30 satellites.

The US military and intelligence services are a major client for BlackSky. NASA, the National Reconnaissance Office, and the National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency have all agreed to sell commercial images to BlackSky.

Customers in transportation, infrastructure, construction, and supply chain management, according to BlackSky, make up the commercial market for its services.

Each of the existing BlackSky Global satellites can take up to 1,000 color photographs each day at a resolution of around 3 feet (1 meter). BlackSky plans to launch the third generation of satellites with a resolution of roughly 20 inches (50 cm) in the future.

The firm processes and analyses images returned to Earth by BlackSky satellites using artificial intelligence and machine learning techniques. According to BlackSky, the algorithms can recognize and identify items in photos without involving people.

SpaceX sells additional capacity on its Starlink flights to give external clients comparatively low-cost trips to space. Transporter missions, which carry dozens of tiny satellites from a variety of the US and foreign clients, are also launched by the launch firm.

BlackSky, a repeat client with SpaceX, had their rideshare launch service handled by Spaceflight, a Seattle-based firm. Previous Falcon 9 flights have launched three BlackSky satellites, including two on a Starlink launch in August 2020.

According to SpaceX’s website, launching a 440-pound (200-kilogram) satellite on a rideshare mission costs $1 million. That is a lot less than any other launch service, even tiny satellite launchers like Rocket Lab’s Electron.

Rocket Lab and other smallsat launch businesses, on the other hand, may launch satellites into orbit on dedicated trips, allowing operators to determine their height and inclination more freely.