For the first time, SpaceX has openly discussed its intentions to utilize Starship to build Mars Base Alpha with experts from NASA and other US organizations.

Except for a few scattered statements on the outskirts of SpaceX and CEO Elon Musk’s major emphasis, Starship, the firm, and its officials have practically never directly detailed how the next-generation fully-reusable rocket would be utilized to establish a permanent human presence on Mars. For the most part, such laser-like concentration on short-term obstacles is admirable.

A half-century of primarily theoretical research has demonstrated unequivocally that establishing a permanent and sustainable interplanetary human colony is impossible without a substantial drop in the cost of access to space.

NASA has spent decades researching, studying, and refining a plan that would cost hundreds of billions of dollars to transport a few humans to Mars for a few months at a time.

Musk unveiled a significant design revision two years after SpaceX declared its aim to develop that next-generation space transportation system, and work on the first steel Starship prototypes began. After three years, SpaceX has completed nine Starship test flights – four short trips and five flights over 10 km (6 mi).

SpaceX completed four of those high-altitude flight tests in 2021 alone, recovered a high-altitude prototype intact for the first time, built the first orbital-class ship and booster prototypes, began testing that ship, and is nearly finished building the first orbital Starship launch site from scratch. In April, SpaceX received a $2.9 billion NASA contract to create a human-rated Moon lander derivative of Starship.

Simply said, SpaceX – and now NASA – have established a solid framework upon which Starship will almost certainly be realized. There is still more work to be done, but SpaceX has mostly overcome the key technological obstacles that towered over Starship/BFR/ITS just a few years ago.

A plethora of Starship ground and flight experiments have conclusively shown that the rocket’s structures, avionics, Raptor engines, exotic means of descent and landing, and hitherto unflown fuel of choice are all ready for orbital flight.

After that, SpaceX will need to demonstrate Starship’s massive, ceramic, non-ablative heat shield technology, mature orbital rocket refueling techniques and technologies, and finally operationalize all of the above to make the rapid launch, reuse, and refueling of the largest rocket in history routine and mundane – something SpaceX has proven to be more than capable of with Dragon and Falcon.

Preparing for Mars

SpaceX has begun to address that issue in a 2021 whitepaper [PDF] submitted to the National Academies’ upcoming Planetary Science and Astrobiology Decadal Survey, with coauthors from NASA Ames, SETI, and a half-dozen top US colleges and institutions.

While that survey alone could have an impact on NASA as it prepares to outline its next decade of space science and determine the ultimate destination of tens of billions of federal dollars, the implications could be enormous, SpaceX also used the paper to describe its plans for early missions to Mars in unprecedented detail.

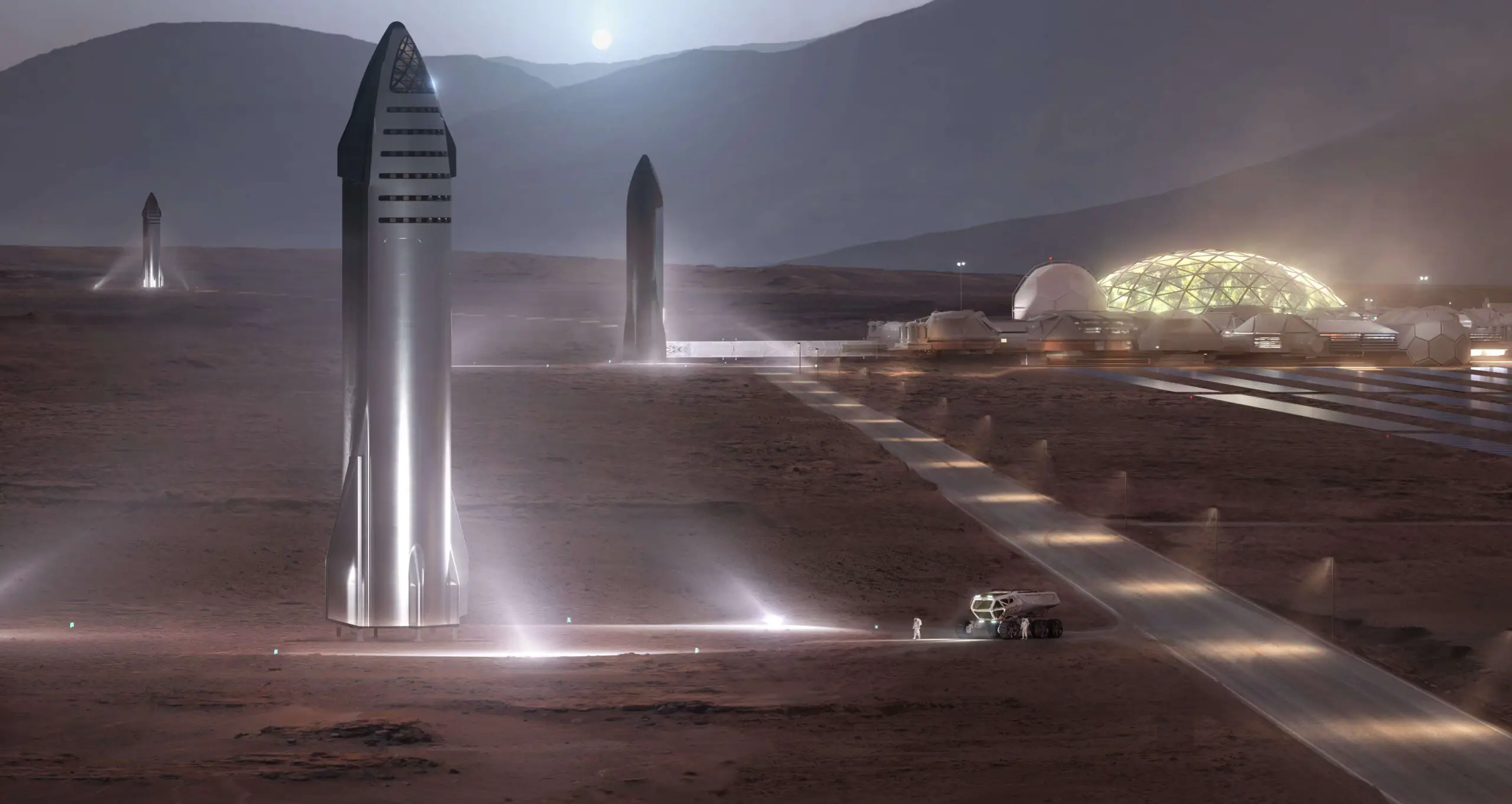

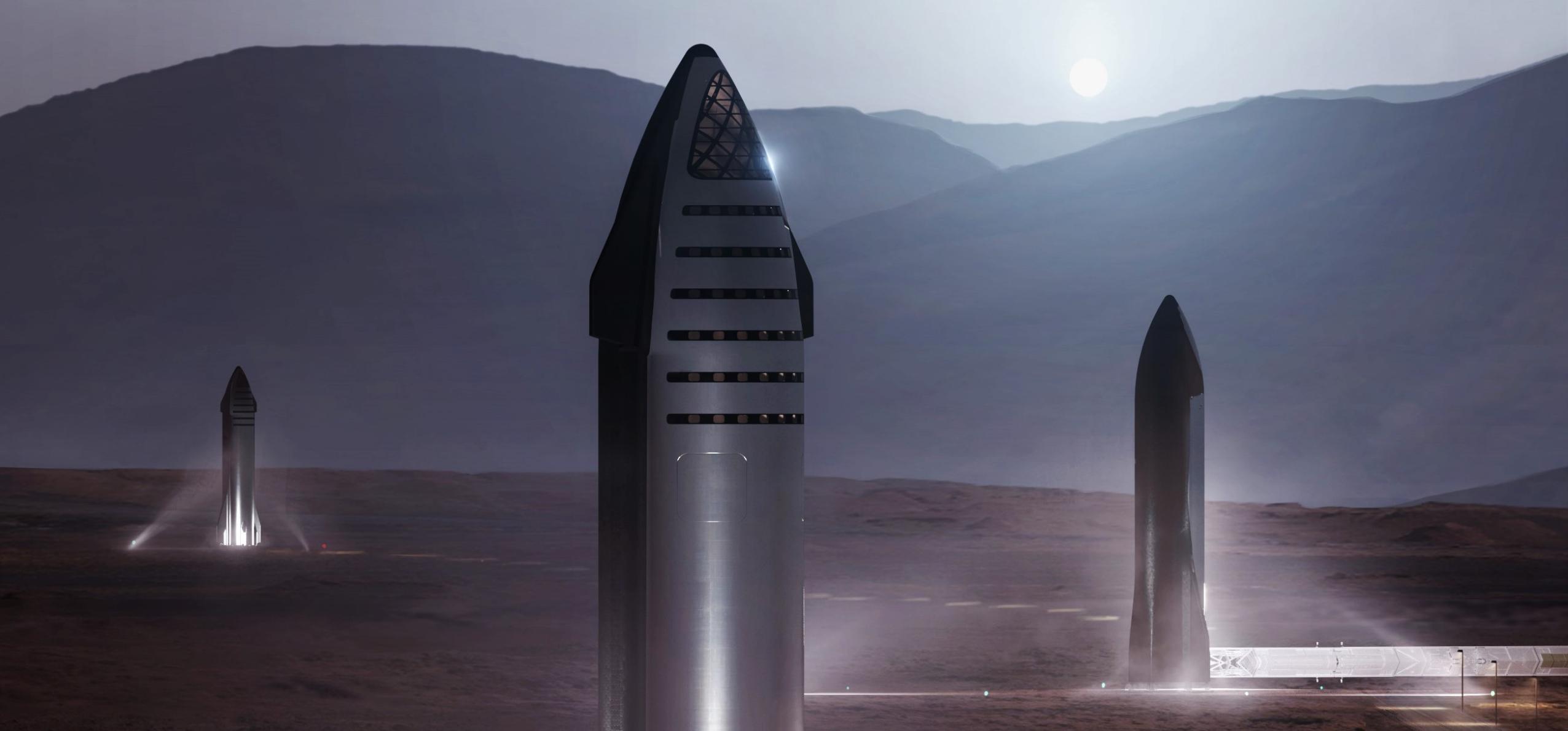

SpaceX will begin the process of building sustainable towns on Mars in a few (relatively) straightforward phases, as has always been the intention. SpaceX plans to send unmanned Starships to Mars as early as the mid-2020s to test the system’s maturity and readiness, as well as “transport considerable quantities of goods to the surface in advance of human arrival.”

Those early trips, which will most likely rely on a variety of robots, will enable SpaceX to evaluate local resources, stage supplies, test technologies for long-duration Martian surface operations, and begin establishing infrastructure — with a propellant plant being the most critical necessity. None of this comes as a surprise. But wait, there is more.

According to the authors, “current SpaceX mission planning [tasks those early uncrewed Starships with delivering] equipment for increased power production, water extraction, LOX/methane production, pre-prepared landing pads, radiation shielding, dust control equipment, exterior shelters for humans and equipment, [and more – all hardware needed to support the first human base].”

Additionally, “humans will likely live on [Starships] for the first few years until additional habitats are constructed,” and “the first wave of uncrewed Starships can also be relocated and/or repurposed as needed to support the humans on the surface,” serving as “valuable assets for storage, habitation, [scientific laboratories], and a source of refined metal structures and resources.”

According to the report, “SpaceX is quickly building Starship to…conduct initial test flights to Mars…as soon as 2022 [or 2024].” He even suggests that SpaceX may send the first Starship(s) to Mars before the rocket’s maiden lunar trip, but then conduct a second lunar mission and land a different Starship on the Moon while the Marsbound ship(s) are still in transit.

The whitepaper is the first time SpaceX (or those acquainted with the company’s intentions) has thoroughly filled out the foundations of its first crewed and uncrewed Starship flights to Mars, and it verifies a lot of well-informed conjecture. Specifically, SpaceX appears to want to load even the earliest Mars-bound spacecraft with supplies.

Even if they do not bring much, the first Martian immigrants — launched in batches of “10-20 individuals” with “100+ metric tonnes” (220,000+ lb) of goods – will repurpose all surviving Starships into pre-emplaced dwellings, storage tanks, and raw material feedstock. Early cargo will concentrate on the manufacture of electricity, water, and propellant, as well as shelters, radiation shielding, and the building of prepared landing sites.

Early colonists will, predictably, establish their initial homes on the surface of Mars inside the Starships that transport them there, making use of a 1100m3 (39,000ft3) pressurized volume currently equipped to maintain hundreds of people alive and healthy in deep space for months at a time.