NASA and SpaceX are still looking into the source of the Dragon spacecraft’s delayed parachute openings, a behavior that has not passed any safety criteria and is not expected to postpone the next crewed flight.

Officials from the agency and the corporation acknowledged on Friday that teams are looking into the parachute release procedure on both cargo and crewed versions of the Dragon spacecraft, the former of which splashed down on Jan. 24 during a resupply mission to the International Space Station.

They verified that the capsule’s fourth parachute failed to open, the second time this has happened during a Dragon re-entry.

On April 15, astronauts Samantha Cristoforetti, Robert Hines, Kjell Lindgren, and Jessica Watkins will travel to the International Space Station on the next Crew Dragon mission, which will launch from Kennedy Space Center’s pad 39A.

Officials said that the mission is still on track for an on-time launch and that the probe is focused on gaining a better understanding of the situation rather than on safety concerns.

In November, four astronauts on the Crew-2 mission returned from the International Space Station and splashed down in the Gulf of Mexico, demonstrating the first trailing parachute occurrence.

The sluggish deployment of the fourth parachute was seen on the live webcast for officials and viewers alike. Just two days after the Gulf of Mexico splashdown, NASA and SpaceX launched Crew-3 with four additional men.

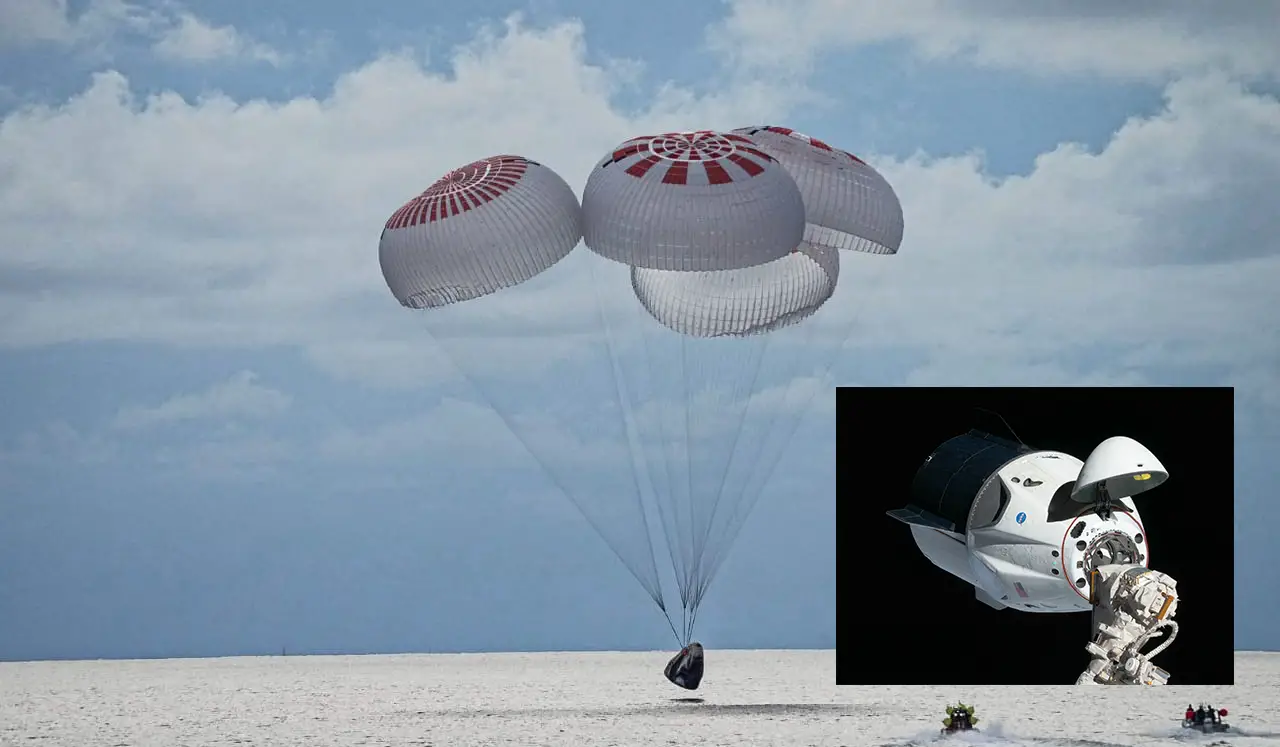

Dragon features four huge parachutes that let the capsule slow down just above the water’s surface. Officials claim that crews may safely land on three because the fourth provides extra safety margin, but that has not been the case so far, since the fourth has failed to deploy in both cases.

The raw data are taken from Dragon, according to a SpaceX spokesperson, indicating optimum descent rates. In other words, the slow fourth chute had no effect on the fall pace.

“You would not even know this was happening if we did not have the footage,” William Gerstenmaier, SpaceX’s vice president of build and flight reliability, told reporters on Friday.

“We are not thrilled with it, even if the system is working well. We will keep investigating to see if we can better understand how the system works and where the flaws are so that we can make it a safer method for workers moving ahead.”

NASA’s Commercial Crew Program manager, Steve Stich, said a few possibilities are now being developed. It is conceivable that the first three parachutes work so well that their aerodynamics prevent the fourth from properly inflating.

“From an aerodynamic standpoint, three of the canopies may shade, if you will, one of the other canopies, and then it simply struggles to inflate at times,” Stich said. “The fact that we observed it on two back-to-back trips is intriguing to us, so we are taking the additional time to investigate the system further.”

“So far, we have not seen anything weird or off-nominal in any of the images,” he added.

For more than a half-century, parachutes have been a source of frustration for aerospace engineers. Back in the Apollo program, capsules were built to safely return with crews even if one of their parachute systems failed.