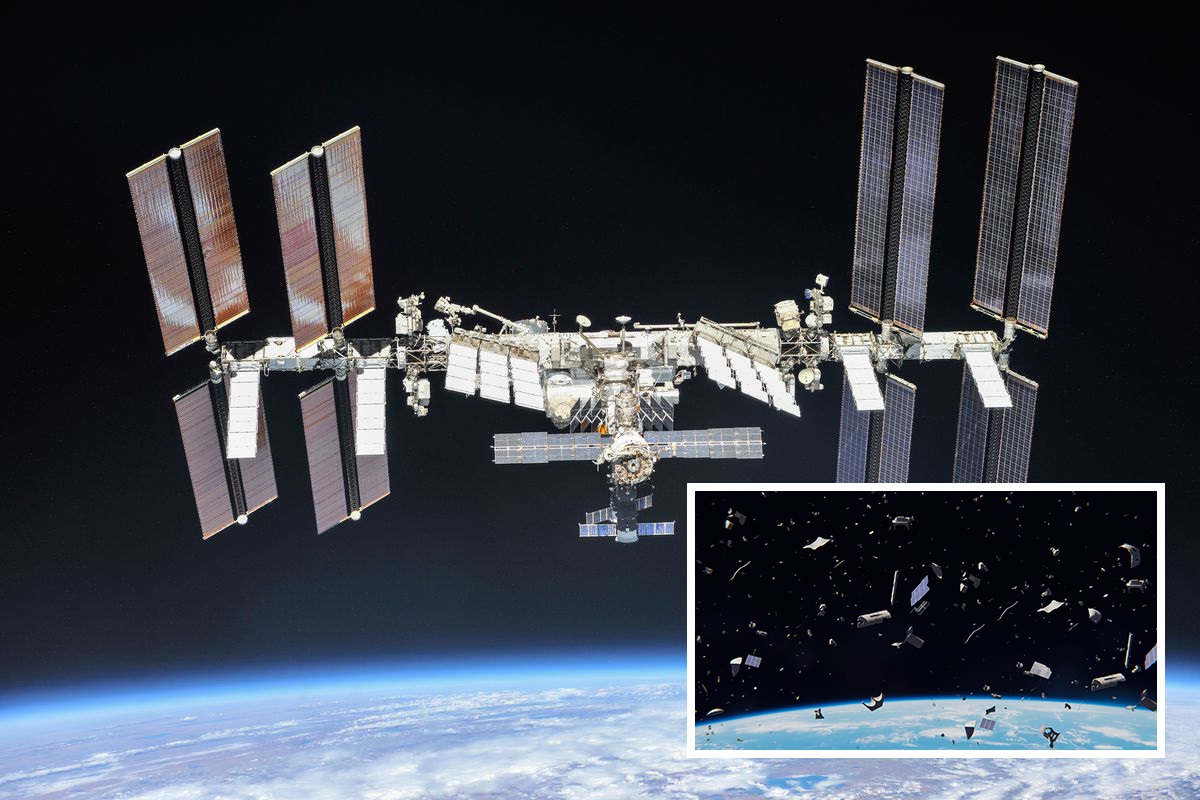

Earlier this week, the International Space Station (ISS) was forced to move out of the line of a probable collision with space trash. With a crew of astronauts and cosmonauts on board, this needed an immediate adjustment of orbit on November 11.

Over the station’s 23-year orbital history, there have been around 30 near encounters with orbital debris necessitating evasive action. Three of these near-misses happened in 2020. In May this year there was a hit: a small piece of space trash punched a 5mm hole in the ISS’s Canadian-built robot arm.

This week’s event featured a piece of debris from the defunct Fengyun-1C meteorological satellite, destroyed in 2007 by a Chinese anti-satellite missile test. The satellite burst into more than 3,500 bits of debris, most of which are still circling. Many have now fallen within the ISS’s orbital area.

To avert the collision, a Russian Progress cargo spacecraft docked to the station fired its rockets for slightly over six minutes. This modified the ISS’s speed by 0.7 meters per second and elevated its orbit, already more than 400km high, by nearly 1.2km.

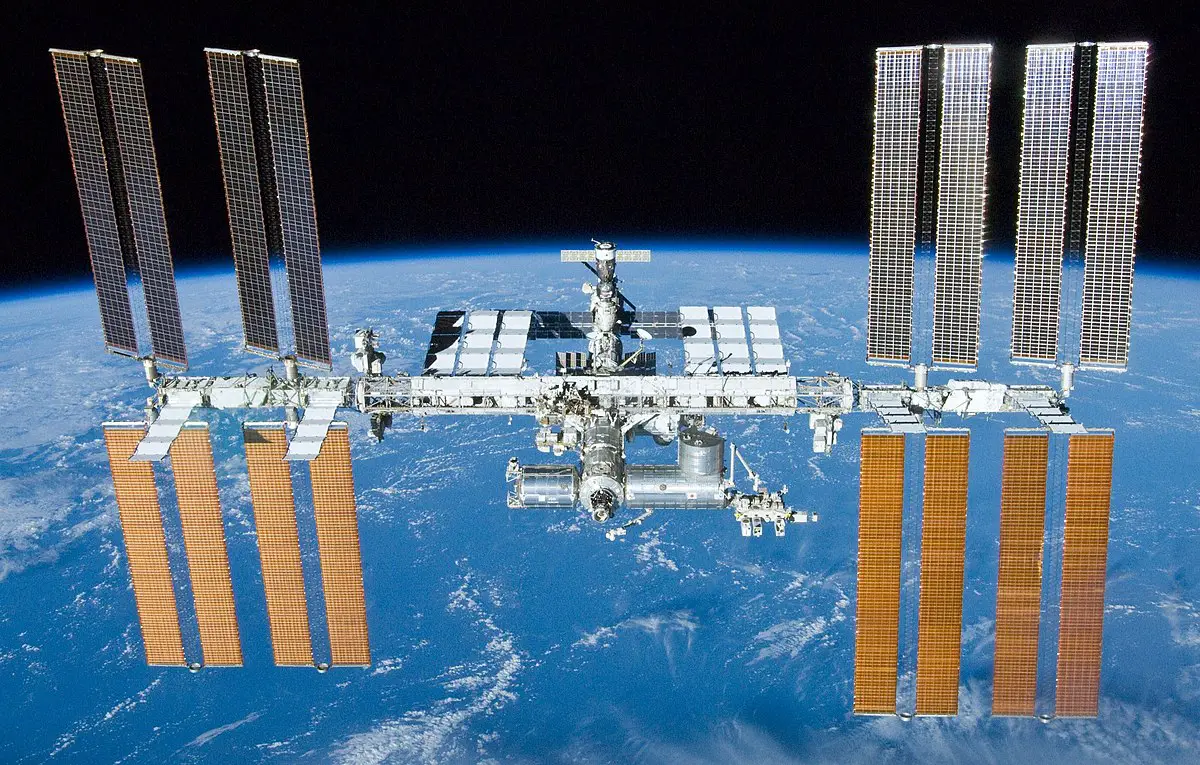

Space debris has become a big hazard for all spacecraft orbiting the Earth, not just the football-field-sized ISS. As well as renowned satellites such as the smaller Chinese Tiangong space station and the Hubble Space Telescope, there are hundreds of others.

As the biggest manned space station, the ISS is the most vulnerable target. It revolves at 7.66 kilometers a second, fast enough to go from Perth to Brisbane in under eight minutes.

A collision at such speed with even a little piece of debris might do significant harm. What matters is the relative speed of the satellite and the junk, so some collisions may be slower while others could be quicker and inflict considerably more damage.

As low Earth orbit grows more congested, there is more and more to run into. There are already approximately 5,000 satellites already functioning, with many more on the way.

SpaceX alone will soon have more than 2,000 Starlink internet satellites in orbit, on its way to an original target of 12,000 and potentially ultimately 40,000.

If it was merely the satellites themselves in orbit, it may not be so awful. But according to the European Space Agency’s Space Debris Office, there are expected to be roughly 36,500 orbiting manmade objects bigger than 10cm wide, such as defunct satellites and rocket stages. There are also roughly a million between 1cm and 10cm, and 330 million between 1mm to 1cm.

Most of these things are in low Earth orbit. Because of the tremendous speeds involved, even a particle of paint may damage an ISS glass and a marble-sized item might breach a pressurized module.

The ISS modules are partially protected by multi-layer shielding to minimize the likelihood of a puncture and depressurization. But there is a danger that such a catastrophe may occur before the ISS reaches the conclusion of its lifespan near the end of the decade.

Of all, no one has the technology to monitor every particle of garbage, and we also don’t possess the capacity to eradicate all that rubbish. Nevertheless, potential ways for removing bigger objects from orbit are being studied.

Meanwhile, almost 30,000 fragments bigger than 10cm are being followed by groups throughout the globe like as the US Space Surveillance Network.

Here in Australia, space debris monitoring is an area of rising attention. Multiple organizations are collaborating, including the Australian Space Agency, Electro Optic Systems, the ANU Institute for Space, the Space Surveillance Radar System, the Industrial Sciences Group, and the Australian Institute for Machine Learning with support from the SmartSat CRC.

In addition, the German Aerospace Center (DLR) maintains a SMARTnet facility at the University of Southern Queensland’s Mt Kent Observatory devoted to monitoring geostationary orbit at a height of roughly 36,000km – the home of many communication satellites, including those used by Australia.

One way or another, we will ultimately have to clean up our space neighborhood if we want to continue to profit from the nearby sections of the “final frontier.”