In what amounts to a privately financed space program alongside Elon Musk’s SpaceX, Jared Isaacman, the wealthy entrepreneur who led the first all-private-citizen crew to orbit in September, has commissioned three further spaceflight missions.

The flights, called Polaris after the North Star, would strive to methodically map new territory in bold, pioneering missions, similar to NASA’s Mercury, Gemini, and Apollo projects at the start of the Space Age.

They would significantly speed commercial spaceflight development in what has become a new age of exploration, in which private firms — and individuals — are claiming the rarefied terrain that was long the exclusive province of governments.

In an exclusive interview with The Washington Post, Isaacman said that the first voyage, which might happen by the end of the year, would attempt to carry a crew of four further than any previous human spaceflight in 50 years and include the first private-citizen spacewalk.

The second voyage would also take place on SpaceX’s Dragon spacecraft, which NASA currently uses to transport humans to the International Space Station.

The third trip in the series, on the other hand, will be the first crewed voyage of SpaceX’s next-generation Starship spaceship, which NASA plans to use to land people on the moon.

The Inspiration4 effort was financed last year by Isaacman, the founder and CEO of Shift4, a payment processing startup. In a journey that earned more than $240 million for St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital, Isaacman and three other private people — strangers before they were selected for the mission — were propelled into orbit for three days.

SpaceX educated the crew, supplied their spacesuits, kept them alive in orbit, and then rescued them from the Gulf of Mexico once they returned to Earth.

The trip reached a height of 367 miles, higher than the Hubble Space Telescope and most space shuttle flights. It was another example of the government’s long-held monopoly on human spaceflight eroding as private businesses grow increasingly skilled and adventurous, with NASA on the sidelines.

“That was a heck of a trip for us, and we are only getting started,” Isaacman said after the Inspiration4 flight, hinting that there could be more to come.

Isaacman told The Washington Post that he had been talking to SpaceX about the Polaris program before the Inspiration4 launch. He was awestruck by the wonder of space travel after the Inspiration4 voyage, and anxious to fly again, he added.

However, he had reservations about continuing the private spaceflights since the Inspiration4 mission, which was documented in a Netflix documentary, had achieved so many goals. He was also concerned that he would not be able to break new ground.

“I adore space, and I would jump at the chance to go back,” Isaacman, who is also an aviation enthusiast and a very accomplished jet pilot, added. “I simply felt that we got a lot done with Inspiration4, and I did not want to take anything away from it until it could have a huge influence on the globe.”

He was not ready to go on unless he was certain that the extra trips would “serve the larger objective of opening up space for everyone and making humans a multi-planetary species, and, hopefully, have a benefit for the things we are attempting to do here on Earth.”

Isaacman and SpaceX did not say how much he paid for the trips, although it is likely in the hundreds of millions of dollars. He also refused to tell how much the Inspiration4 mission cost, other than to say it was around $200 million.

Along with the first commercial spacewalk, Isaacman said that the first Polaris mission will aim to “travel farther than anybody has gone since we last stepped on the moon – in the highest Earth orbit that anyone has ever flown.”

According to NASA, the record was achieved in 1966 by the Gemini 11 crew, who went to an altitude of 853 miles, the highest for any non-lunar crewed mission.

The mission, which would take off from Florida’s Kennedy Space Center, would need a Federal Aviation Administration license. However, while providing such certification, the FAA considers only the safety of persons and property on the ground, not the hazards that their operations in space can bring to the crew.

The crew would also conduct a space test of SpaceX’s Starlink laser-based satellite communications system. Starlink satellites now broadcast Internet communications to remote regions on Earth, but SpaceX hopes to utilize the technology for human spaceflight trips to the moon and Mars in the future.

The university and research institutions involved in the program include the University of Colorado in Boulder, Embry-Riddle Aeronautical University, Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory, and the United States Air Force Academy.

Before and after the spacewalk, Isaacman said, the first mission will undertake research to see how individuals deal with decompression sickness and why it differs. The crew would also collect information on how radiation affects the human body, as well as how microgravity affects astronauts’ minds and eyes.

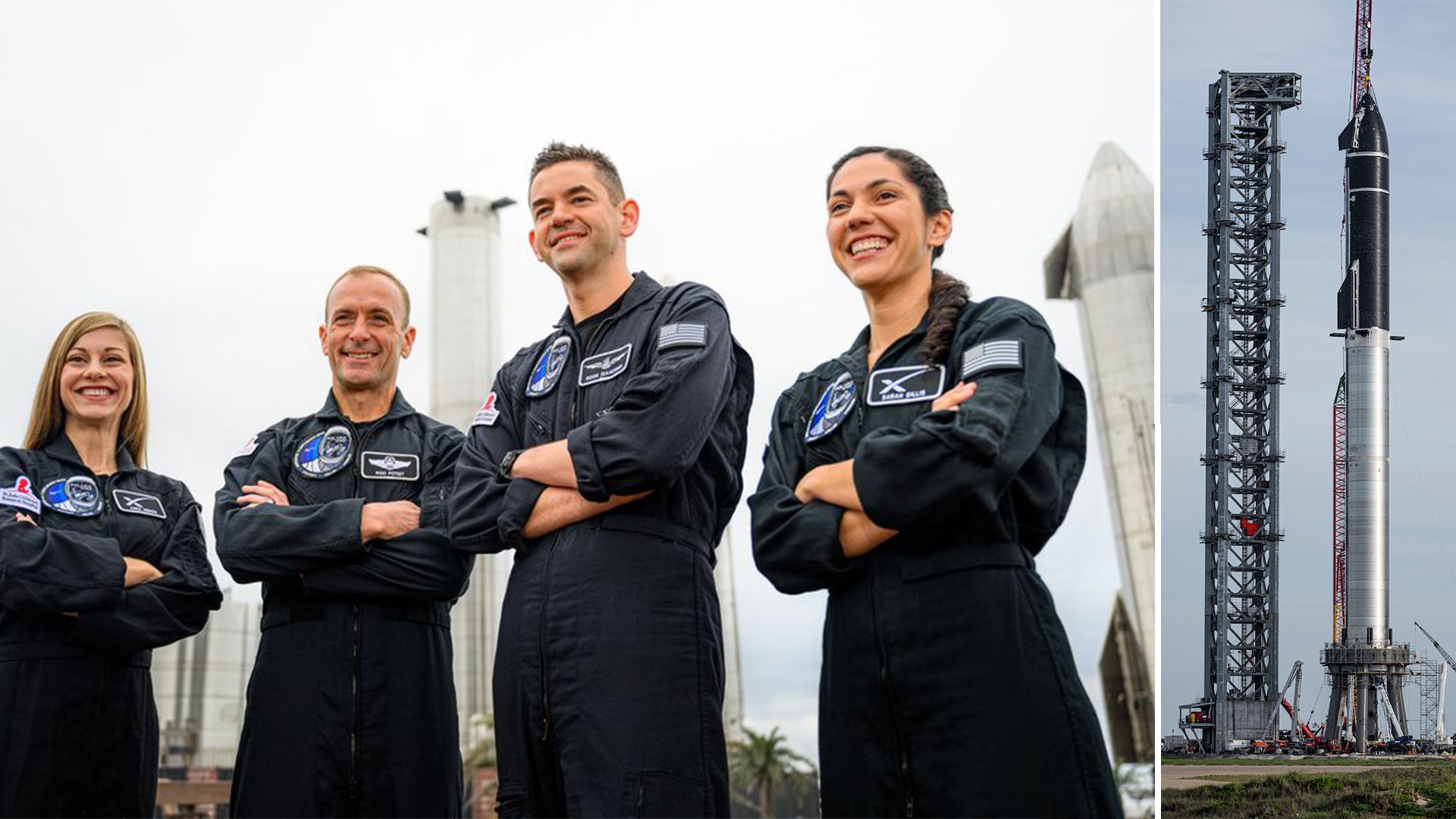

The first Polaris flight, known as Polaris Dawn, will be led by Isaacman. Scott “Kidd” Poteet, a former Air Force pilot who served as the mission director for Inspiration4, and Sarah Gillis and Anna Menon, two SpaceX lead operation engineers who assist train astronauts for missions on the company’s Dragon spacecraft, will join him.

During the Inspiration4 trip, the four got to know one another and now have “a foundation of trust they can build upon as they take on the difficulties of this mission,” according to the crew.

Menon is married to Anil Menon, SpaceX’s first flight surgeon, and a NASA astronaut candidate. “The first words out of his lips were, ‘Mama, when are you going to become an astronaut?'” when the couple informed their 4-year-old son that Anil Menon was going to be a NASA astronaut. In an interview, Anna Menon said.

Isaacman invited her to join the Polaris crew a few weeks later, and she will now likely reach space before her husband.

The Polaris Dawn crew plans to do a spacewalk in addition to achieving an altitude record, which would be a first for an all-private-citizen spacecraft.

The crew would have to put on pressurized spacesuits and carefully depressurize the cabin before opening the hatch at the top of the capsule since the Dragon spacecraft lacks an airlock. Then, while still tied to the vessel, they may climb outside and float in space.

Isaacman said it was still up in the air whether everyone would have a chance to go outdoors, and that it was just one of many intricacies of the operation that needed to be ironed out.

SpaceX is creating more sophisticated spacesuits to undertake the spacewalk, which will keep the crew safe in the vacuum of space.

The spacewalk would add another element of difficulty and risk to an already dangerous undertaking. NASA astronauts practice for their spacewalks on the International Space Station for months in a large pool at the Johnson Space Center in Houston, simulating the weightlessness of space.

Stepping outside the space station is one of the most hazardous things an astronaut can do, and it has never been done by non-professional astronauts before.

Despite this, the Polaris crew expressed confidence that they would be able to benefit from NASA’s expertise and that SpaceX would be able to assure their safety during extravehicular activities, or EVAs.

“NASA has been doing spacewalks for a long time, and they have accumulated a lot of information in the process,” Gillis said. “We spoke with previous NASA astronauts and current NASA astronauts about their EVA experiences and how you really go about doing this.” Having seen it myself, I have complete faith in SpaceX’s procedures, including verification, testing, and the very thorough examination of everything.”

In the months ahead, Isaacman said, the crew will share more information about the mission — and the two that will follow — with the public. He said that the crews for the last two flights had still to be chosen. The initiative, however, will “culminate in the first crewed flight of Starship,” according to Isaacman.

The huge spaceship that SpaceX is developing to transport humans to the moon and Mars is known as Starship. NASA gave SpaceX a roughly $3 billion contract last spring to assist in the development of the spaceship, which will be used to put people on the moon as part of NASA’s Artemis program. The spaceship is being developed and tested at SpaceX’s Starbase, a huge site in South Texas.

If Isaacman and his crew are the first to fly in it, it will be a watershed moment in human spaceflight. For the initial crewed test flights of new rockets, NASA usually turns to its most experienced astronauts. Veteran NASA astronauts Bob Behnken and Doug Hurley, for example, were the first to test out SpaceX’s Falcon 9 rocket on its maiden human mission.

Starship will fly several times before the first crewed voyage, according to Isaacman. “I anticipate them to perform an awful number of flights and collect a lot of data before the first human people fly on board that spacecraft,” he said.

The fact that a private citizen crew will be the first to fly Starship is not a dig at NASA, but rather a statement of how space exploration is changing fundamentally, according to Isaacman.

“NASA has paved the road for everyone,” Isaacman said emphatically. “We are all here now as a result of their achievements and sacrifices from a long time ago. But what we are witnessing here is that this is not just a NASA problem. There is a lot of private money attempting to make the SpaceX dream a reality.”

Source: WashingtonPost